Sharan Jhangiani

← Back to all postsAn NLP Addition to the Data Washing Machine

August 23, 2019

Original Post: Medium

This post is a continuation of a previous post by Catherine Nelson in the Concur Labs Data Privacy series, explaining her approach to data privacy, the Data Washing Machine.

Introduction

When I came around to Concur Labs earlier this summer as an intern looking for a project, I never imagined that I’d become so invested in the problem of data privacy. Yet, when introduced to the Data Washing Machine, a privacy tool developed by Concur Labs,* *I was captivated by the necessity and importance of the project at hand.** **This is a system that “targets and removes personal data in natural language, i.e. long strings that consist of human-readable text”.

As previously explained in this post, at SAP Concur, within strings of data, there are often copious amounts of PII that we don’t need. Rather than taking a “one size fits all” approach to removing this data, the Data Washing Machine was built to allow users to remove only the aspects of PII that they deem necessary for the security and safety of their data. The privacy dial, illustrated above, shows the types of PII that can be removed from this system, with those types that are most identifying of an individual person at the lowest levels.

Problem

Upon picking up the project, the Data Washing Machine used three methods for removing PII: regular expressions, named entity recognition models and custom machine learning models. While these methodologies worked well in many circumstances my task was to work on improving one of the problems faced with the Regular Expression methodology: picking up poorly formatted numerical data. This is particularly relevant for certain levels on the privacy dial: #2, the SSN, #4, the phone number, and #6, the zip code.

.](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*FhiIHJHOln2yaMDdq707LA.png)

Privacy Dial is used to pick the level of washing wanted within cleaning the data. Illustration by Jessica Park.

For example, if we would like to remove social security numbers from the text data, the number is usually formatted with nine digits, like this: “AAA-GG-SSSS.” However, in conversation or natural language, often we share aspects of our PII, such as the last four digits of our social security number, instead of a perfectly formatted number. I wanted to find a way to leverage contextual dependencies to remove data in these instances.

Methodology

When analyzing natural text, there is a tremendous amount of value in understanding grammatical patterns. The biggest thing I focused on was simple sentence structure, and how to predict where a PII value would most likely appear in a sentence. After looking at numerous examples, I was able to make 2 assumptions to base our model on:

-

A sentence is centered around a single verb, with a corresponding subject and attribute.

-

There will be a direct reference to the element we want to remove.

Using these two assumptions, I moved into the more technical part of the problem. I leveraged the spaCy tokenizer to break down the sentence and provide us with insight into the dependencies, parts of speech, and other information regarding the sentence structure. With this tokenizer, I was able to create an approach to solving the problem that I call “Dependency Tree Recognition”.

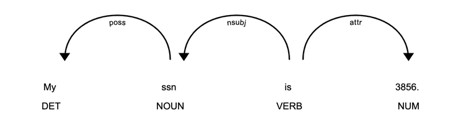

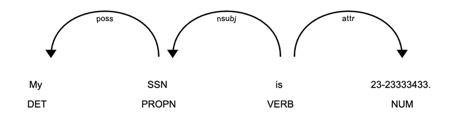

When breaking down a sentence using the spaCy tokenizer, we are given a resulting output that looks like this:

A spaCy dependency tree visualization.

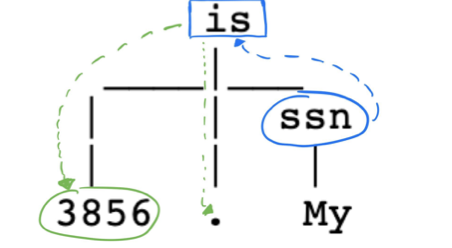

As previously mentioned, the approach to this problem is detecting the direct reference to an element that we want to remove, and then leveraging the sentence structure to predict exactly where that PII is. In the image above, the “VERB” object is acting as the head of the tree, with the reference to the element “SSN” and the element itself as children. The process we use is simple tree iteration, searching for the element reference, iterating up to the “VERB” attribute, and then looking in the rest of the children for a numerical attribute value.

Dependency tree iteration to find the element to be removed.

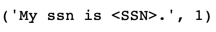

While this approach wasn’t perfect, it was sufficient to provide a *~15%** improvement in detecting PII that is poorly structured.

The resulting output from the model after the data is removed.

Problems

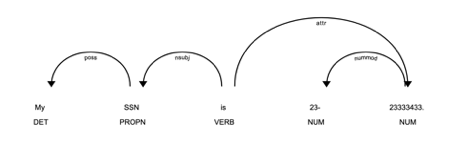

As with any project, there are a series of problems that we run into. One of the problems we were challenged with tokenization of numbers that were formatted with hyphens within them.

A spaCy dependency tree showing tokenization error.

As you can see, the tokenizer breaks the singular numeric element into 2, creating a problem in our approach where we only detect one of the numerical attributes, hence only mask half the PII. In order to combat this, I simply split the sentence into tokens using whitespace. This is a great simple solution to the problem, as it leaves the element containing the PII as one, allowing the model to work.

An updated spaCy dependency tree using WhitespaceTokenizer to show fix.

Conclusion

With the introduction of the Dependency Tree Recognition approach, the Data Washing Machine now identifies poorly formatted PII based on the sentence syntax, which is a large improvement over simply using regular expressions. In a problem space such as privacy, every improvement made is essential, and the opportunity to have contributed to such an important project leaves me proud.

As my summer internship comes to a close, I hope to continue exploring data privacy, and have full expectations that the Data Washing Machine will be at the forefront of the technical solutions available, leaving everything squeaky clean!